This experience report was originally published at the Agile 2019 Conference.

Introduction #

When we first heard about mob programming it sounded preposterous but also intuitive, radical but familiar. Like many teams who have tried mob programming, we were intrigued by the stories we'd heard. We were also searching for fresh ideas that might help us relieve nagging problems. How do we spread knowledge amongst teammates? How can we complete reviews faster and improve flow? How can we amplify fun and improve quality, even during stressful times? After some practice, mob programming helped us improve in these areas and more, but it took time and practice to become an effective mob. Our greatest improvements began when we started paying attention to emergent patterns of interaction among individuals in the mob. What follows is a sample of lessons from our experiences presented as a collection of patterns for mob programming.

About Mob Programming #

Mob programming is an approach to creating software in which the whole team works together on the same thing at the same time [1]. Woody Zuill's experience report introduced mob programming to the world and shared a set of patterns and practices his team used to work collaboratively as a single group, a mob. The core patterns include sharing a single keyboard and computer, swapping every 15 minutes, and promoting respect in personal interactions across the team [1]. Since then, other teams have shared their experiences with mob etiquette [2], scaling the practice [3], remote mobbing [4], and measuring productivity [5], as well as swarming patterns and benefits [6].

Thinking about the lessons from these experience reports and reflecting on our own practice we have come to believe that, at the heart of every effective mob there is a group of people working from a place of mutual respect to deliver the best software they can, as fast as they can. Effectiveness of a mob is ultimately determined not by the tools a team uses but by how well teammates communicate with one another.

Discovering Patterns #

A pattern is a repeatable solution that emerges in response to a specific problem in a particular context. Christopher Alexander is often credited with popularizing the idea that patterns should be cataloged so others may reuse and learn from them. His book, A Pattern Language: Towns, buildings, construction, outlined 253 common forms for organizing regions, cities, neighborhoods, and buildings [7]. His book set the tone for pattern catalogs that followed. Eric Gamma and friends introduced one of the first sets of design patterns to the software world with their book, Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software [8]. Patterns codify knowledge into a reusable package that is easy to share with others thus creating a language everyone may use to describe ways of working, solutions, and even problems themselves.

Our teams are generally quite comfortable with patterns. We apply patterns while programming and designing architectures. We look for patterns in our code so we can extract and share them with teammates. We even record design decisions using Architecture Decision Records (ADRs), which roughly follow the form of a pattern [9]. It seemed natural for us to use the same principles that we use to design software systems to also design our software development methods.

Our mob programming patterns started as basic observations about how our teams worked. After a few mobbing sessions we noticed consistent working and communication styles emerging. One night over beers while talking shop and swapping stories about our new teams, it quickly became obvious there was significant overlap in how our different teams mobbed. We also noticed some interesting differences. As one idea led to another, we decided to try our hand at formulating our observations as structured patterns.

For each potential pattern, we try to articulate three basic parts. The context describes the situation in which a pattern takes place and the general problem the team faced. In response to this problem, we apply a solution that works within the constraints of the context. As a result of applying the solution, there are consequences, both positive and negative, which describe a new context that is a direct result of the solution.

As we recorded the patterns that we discovered, our mobbing began to evolve. Instead of reacting to a situation, we started to intentionally choose how to direct our mobs. Reflecting on the way we work and codifying our observations as patterns helped us become better at mob programming.

About the teams #

We've been practicing mob programming off and on for over one year. In that time, we've mobbed with three different teams in both an "on demand" context as well as full time. While we were both new to mob programming, we already had positive experiences with pair programming, test-driven development, and several other technical practices that can trace their roots to Extreme Programming (XP) and its sibling Agile methods. Michael has been developing software for over 15 years while Joe has worked in the field for just over three years.

We timidly dipped our toes into the mob programming waters with "Mob Mondays" in early 2018. Our team at IBM was co-located and mobbed intermittently through the fall of 2018, when Michael left IBM and the team. Shortly after Michael's departure, Joe also joined a new team within IBM. Both of us felt mob programming was interesting and had many positive benefits that we wanted to explore with our new teams.

After leaving IBM, Michael joined LendingHome, a four-year-old FinTech start-up with offices in San Francisco, CA and Pittsburgh, PA. LendingHome is the leader in bridge-style mortgage loans. The LendingHome Pittsburgh team was responsible for maintaining and extending a large Ruby on Rails application. While the nine person team was experienced, with an average of over seven years in the software industry, Michael's new teammates were new to LendingHome and the mortgage domain. As a result, the team often lacked the context, in either the system or domain, needed to complete work. The LendingHome Pittsburgh team meets as a mob as needed, up to several times each week to work on backlog items together.

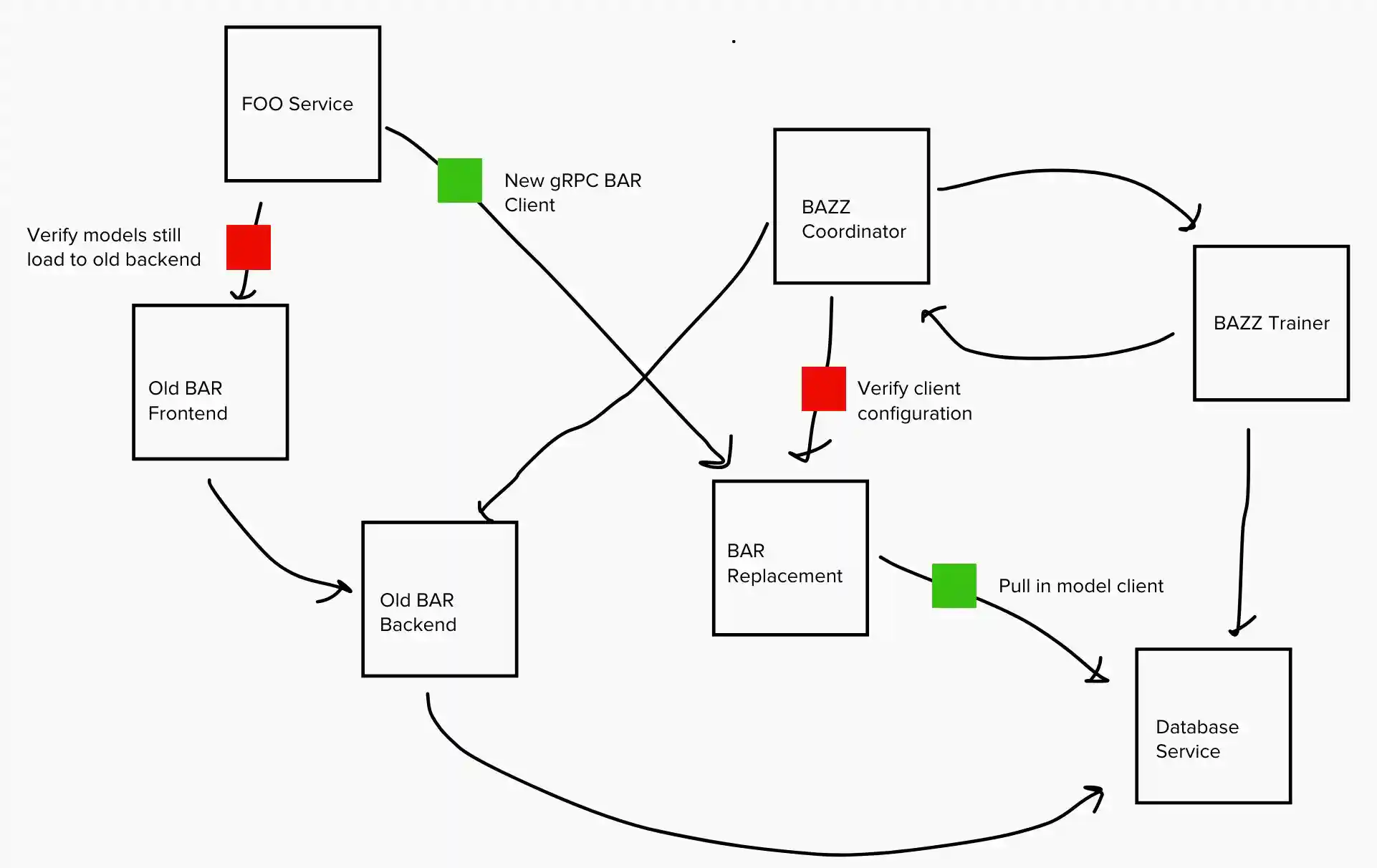

Meanwhile, Joe joined the new IBM Document Ranker Team as team lead. This new team's first mission was to port legacy machine learning systems to newer frameworks supported by the Watson platform. This involved a healthy mix of development and operations work, which was a change for most of the team. The team was relatively fresh, with an average of three years of professional experience. They were also split geographically between Austin, Pittsburgh, Yorktown, and Raleigh. The IBM Document Ranker team immediately began mobbing full-time as a way to get to know each other and learn the codebase. Mob programming stuck, and the team continues to mob daily on one backlog item at a time.

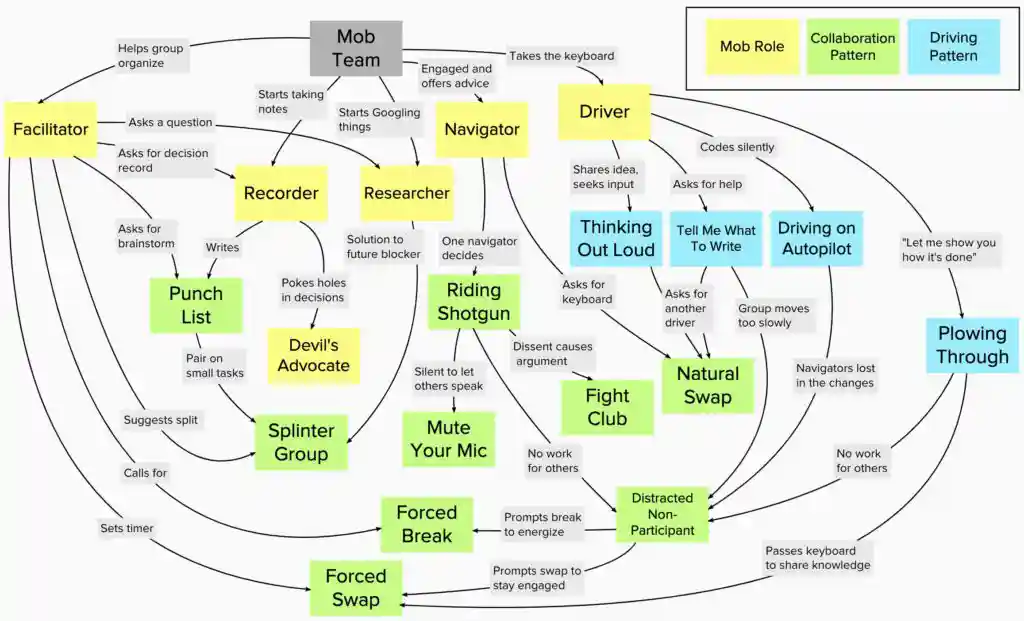

In the following sections we will share the patterns we discovered across both the LendingHome Pittsburgh and IBM Document Ranker teams. For this report we chose to focus on patterns that seemed to happen frequently, patterns that we haven't been documented elsewhere, and patterns that come with an interesting story. The pattern names in the following sections are formatted to

Mobbing Roles #

In nearly every mobbing session across both teams we noticed individuals fill specific roles within the mob. Some of these roles helped the mob move forward more smoothly. Others emerged in response to a specific need. What we found most interesting was that there are more roles operating within a mob than only the

Pattern: Facilitator #

In our experience, mob programming is not a natural process for many developers. Both of our teams enthusiastically participate, but none of us really knew how to mob in the beginning. Some developers in the mob were experienced pair programmers while others had done very little collaborative coding. This mixed bag of experience, combined with competing priorities, varied working styles, and the typical banter that seems to accompany any group of software developers in an enclosed space, creates fertile ground for disruptive behaviors.

All of the cited experience reports on mob programming emphasize the importance of mutual respect among members of the mob. As some teams have reported, experienced mobs can self-regulate easily when the environment and context are right. In our experience, this ideal is a learned behavior. While respect is a prerequisite for mobbing, sometimes a gentle prod for the group to focus, move forward, or pipe down is just what is needed. In most of our mobbing sessions, a

We have never assigned a

On our teams, especially in the first several weeks after introducing mob programming, we often filled the role of the

Pattern: Recorder #

When a mob is running smoothly, we noticed there can be many things happening simultaneously. The driver writes code in collaboration with the

Like the

The documents a

Collaboration Patterns #

Working together as an effective mob takes practice. While trading stories we learned that each team has uncovered different ways of working together. Most of the practices we discovered focus on organizing work and improving participation. We think these patterns emerged in response to an innate desire everyone has to ensure the mob is productive and efficient. Many teammates feel at least some anxiety that mob programming might be perceived negatively by managers and co-workers unfamiliar with the practice and so want to put the best foot forward as possible. We've categorized these ways of working as collaboration patterns. In this section we describe the

Pattern: Punch List #

Across both teams we've seen situations where members of the mob invent different approaches for tackling a problem. It's easy for people to come up with new solutions or focus on different aspects of a problem such that picking an approach is challenging. There is always something to fix and a different way to solve a problem.

When competing ideas for what to work on next begin to pile up, we record them in a

We've noticed that recording ideas in a

Both of our teams practice some version of the punch list. In addition to

Anti-Pattern: Ridin' Shotgun (a/k/a Dominate the Mob, Boosting your Mic) #

To "ride shotgun" means to sit in the front passenger seat of the car, next to the driver. The term originates from the American Old West when the person sitting next to the stagecoach driver literally held a shotgun to protect the wagon from bandits. In modern times, a person riding shotgun has an inordinate amount of control over the car's environment. They are uniquely positioned to adjust everything from the radio to the temperature controls. Often this person is also given sole navigation duties.

During some of our mobbing sessions we've noticed that sometimes one person just talks too darn much. When a member of the mob assumes sole command over the group's direction, they are

When someone is passionate and knowledgeable about a topic, it can be easy for them to dominate a group conversation. This seems to be especially true when the rest of the mob is less knowledgeable or might simply be trying to get a task completed. We think that

In some mobs we've seen the person who emerges as a

Pattern: Mute your Mic (a/k/a Choose not to Dominate, Take a Back Seat) #

The Doc Ranker team is almost fully distributed. One day the mob had a particularly difficult start to the session. To keep things moving forward, Joe, much to his chagrin, did most of the talking while the group remained silent. In an act of desperation to jump start participation, Joe muted his mic, leaned back in his chair, and waited to see what happened. After what felt like an eternity, someone else in the mob broke the silence by suggesting an idea to move the team forward. With the ice broken, more

We've seen mobs remain mum for many reasons. Sometimes people become

One technique we use to encourage participation is to force it by asking individuals who are sharing more than others to

When we take a back seat, we sometimes shift into a different role to keep our minds busy and give the mob, and ourselves, a chance to recalibrate. Instead of jabbering on and dominating the mob at the expense of collaboration, we may slide into a new mob role such as a

Driving Patterns #

As originally presented by Woody Zuill, the mob's knowledge flows through the

Given the

Pattern: Plowing Through #

One situation we've seen arise multiple times across both our teams is for the

When a

On the whole we think

Pattern: Tell me What to Write #

Sometimes when we assemble as a mob, only one or two people have the necessary context about our goal to kick things off. This can happen for a few reasons. For example, a new teammate doesn't yet know the tech stack, or an old teammate was one of the last programmers standing on a project. More often, only one or two people from the current mob explored requirements ahead of time and have the background needed to start a work item. Presented with this situation,

In our experience, seeking help from the mob in this way can be quite thrilling. Engaging the mob is a great way to encourage participation. It can be a fun, "I don't really know where we're going but I'll learn while we go there!" experience. Telling the

| Pattern | Category | Gist |

|---|---|---|

| Facilitator | Mob role | Volunteer who helps the group stay focused and to help resolve differences of opinion. Typically the driver does not take this role. |

| Recorder | Mob role | Volunteers who capture notes such as context or design decisions on behalf of the mob. |

| Researcher | Mob role | Volunteers who seek out information in real-time that is required for the mob to move forward. |

| Navigator | Mob role | Direct the driver in what to do. Members of the mob not currently driving are assumed to be a navigator. Navigators can contribute to the mob in many ways. |

| Driver | Mob role | The person currently at the keyboard, capturing the thoughts of the navigators as everyone works to solve a particular problem. |

| Devil’s Advocate | Mob role | A navigator who takes a contrarian position to help make the mob’s designs stronger. |

| Punch List | Collaboration | A task list used by the mob to track work items and select what to work on next. Punch lists can be text-based or graphical. |

| Splinter Group | Collaboration | One or more members of the mob who break away from the main group to complete a routine task. Splinter groups can also investigate alternatives for review by the whole mob. |

| Ridin’ Shotgun | Collaboration | A navigator who solely dictates the mob’s work to the exclusion of other navigators. |

| Mute your mic | Collaboration | A navigator chooses to temporarily remain silent as a navigator to give other navigators a chance to contribute. Used as a way to kick start a slow mob or prevent one person from dominating the mob. |

| Fight Club | Collaboration | A situation in which two or more participants fight over the direction of the mob with total disregard for the guiding principles of mutual respect and consideration. Extremely harmful to the mob, considered an anti-pattern. |

| Natural Swap | Collaboration | A new driver takes the keyboard without prompting by either a member of the mob or timer at a “natural” break in the work, such as after a test passes or a refactoring step is completed. |

| Forced Swap | Collaboration | A new driver takes the keyboard after being prompted by either a member of the mob or a timer. |

| Distracted non-Participant | Collaboration | Navigators who are present in the mob but otherwise do not participate, perhaps distracted by other work. |

| Thinking Out Loud | Driving | The driver articulates their current thinking as they are the prevailing expert in the room or see the path forward. |

| Tell me what to write | Driving | A prompt drivers will sometimes use to engage help from navigators, inviting someone from the mob to direct the driver. |

| Driving on Autopilot | Driving | A driver who proceeds without inputs from the rest of the mob. |

| Plowing Through | Driving | A driver who, with the support of the mob, works on the task at hand with the intent of completing it as quickly and painlessly as possible. Often combined with the thinking out loud pattern. |

Conclusion #

In "Mob Programming: a Whole Team Approach," Woody Zuill presented one way of practicing mob programming that was born from three years of experimentation. That experience report outlines a basic framework for good mobbing practice, but as we've learned over the past year or so, there is still much we can all learn about mob programming. We've also learned that there are many different paths that lead to success. There is no one way to "do mob programming." While there is no one best way, there are many practices that seem to work well. The applicability of any particular practice is highly dependent on the context. There seem to be many practices that work most of the time. There are also some, such as the plowing through pattern, which are negative in most contexts but can sometimes be useful. Context rules the day! In our experience, patterns are a fantastic vehicle for describing how we work in context.

Codifying the way we work as patterns has proved to be a powerful tool for honing our practice. The mere act of teasing out the patterns seems to make the group more introspective and intentional about what we do and how we do it. Instead of guessing what to do next, we pull the most appropriate pattern relevant to the present context from our catalog of patterns. Even better, patterns are easy to capture and share, so we can take advantage of what other teams are learning too. In the hope that we might jump start our collective intelligence about mob programming and make it easier for other teams to build on what we've learned, we have started a GitHub repository to collect mob programming patterns. We seeded the catalog with our set of patterns. We invite you to join us by adding new patterns (and anti-patterns), trying out patterns with your teams, and by sharing your experiences with mob programming. We encourage you to build on our patterns. Try them out for yourself. Maybe avoid the anti-patterns we uncovered. Share your stories and mob on.

Acknowledgements #

Thank you to all of our teammates for being willing to give mob programming a try. Huge shout out to our shepherd, Rebecca Wirfs-Brock. We've consistently challenged experience report style norms and we are extremely appreciative for Rebecca's support and guidance as we experiment. We also would like to thank all the fine craft brewers whose tasty beverages provided at least part of the foundation upon which our pattern discoveries were built.

References #

W. Zuill. "Mob Programming — a Whole Team Approach," Proceedings from Agile2014, August 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.agilealliance.org/resources/experience-reports/mob-programming-agile2014/. [Accessed 24 May 2019].

J. Kerney. "Mob Programming — My First Team," Proceedings from Agile2015, August 2015. [Online]. Available: https://www.agilealliance.org/resources/experience-reports/mob-programming-my-first-team/. [Accessed 24 May 2019].

C. Lucian. "Growing the Mob", Proceedings from Agile2017, August 2017 [Online]. Available: https://www.agilealliance.org/resources/experience-reports/growing-the-mob/. [Accessed 24 May 2019].

S. Freudenberg and M. Wynne. "The Surprisingly Inclusive Benefits of Mob Programming," Proceedings from XP 2018, May 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.agilealliance.org/resources/experience-reports/the-surprisingly-inclusive-benefits-of-mob-programming/. [Accessed 24 May 2019].

A. Hamid and A. Noaman. "Experimenting with Mob-Programming," Proceedings from Agile2018, August 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.agilealliance.org/resources/experience-reports/experimenting-with-mob-programming/. [Accessed 24 May 2019].

D. Arsenovski. "Swarm: Beyond pair, beyond Scrum," Proceedings from Agile2016, August 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.agilealliance.org/resources/experience-reports/swarm-beyond-pair-beyond-scrum/. [Accessed 24 May 2019].

C. Alexander. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, Oxford University Press. 1977

E. Gamma, R. Helm; R. Johnson, and J. Vlissides. Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison-Wesley Professional. 1994

M. Keeling and J. Runde. "Share the Load: Distributing Design Authority with Lightweight Decision Records," Proceedings from Agile2018, August 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.agilealliance.org/resources/experience-reports/distribute-design-authority-with-architecture-decision-records/. [Accessed 24 May 2019].